The Road Home: The Journey Towards Living My Purpose

I’d lost count of how often that nagging question ambushed me. As I did every workday, I charged down the narrow road to the highway to work, my brain on fire. Not with ideas and energy but with a morbid calculation that had become routine. It was so routine that I’d even gone through my old college physics books to refresh my memory on kinetic energy.

As I eyed the thick, ancient trees lining the road, that question which had gripped my mind so often came up yet again:

“What’s the optimal speed to hit one of those trees so I don’t kill myself but hurt myself enough to get a three-month break from work?”

I’d “made it”, but my heart was crying.

I was 32, had a six-figure salary running a $100 million sales department for the coolest IT company at the time, and 65 people working under me. Most people would say that I’d made it. And yet, here I was, considering self-harm as my only escape. Maybe I needed a break from work, not hospitalisation.

Except, I was already taking all the breaks the system allowed. That’s to say, 25 days of paid holidays, but never more than 2 weeks straight, where you spend the first few days fidgeting nervously while trying not to check your work emails on your phone every couple of minutes, and the last few days with a creeping sense of nausea at the thought of going back to the office.

Sandwiched in-between are those fleeting, euphoric moments where you tell yourself, “Screw slaving away as a corporate drone, let’s sell all our things, move here and open a bed and breakfast.” I’m pretty sure I said some version of those words at least once every vacation I took.

To be fair, though, work wasn’t all bad. The best parts of my job involved collaborating closely with my team members, engaging with them and challenging them to overcome their fears, nudging them in the right direction, and seeing them grow and prosper as individuals. That energised me, making me feel like I was doing something worthwhile. But such moments were very rare. My reporting requirements kept me buried under spreadsheets for days, pushing numbers up the command chain so the top management could further “motivate” my department with targets, metrics, and benchmarks.

The other problem was that I’d chosen to be there. No one was forcing me. And yet, I felt like a hamster on a wheel, always running but going nowhere.

I left my heart at home every workday and replaced it with my laptop. From 8 a.m. to 7 p.m., I was busy with tasks, responsibilities, and obligations that meant little to me. Days, weeks, and months disappeared in a hazy blur of repetitive motion. It was making me sick to my stomach. But I had no idea how to get myself off the wheel without throwing myself off and crashing into a tree. And the wheel was spinning faster and faster.

I needed something to happen. To dig deep, close my eyes, and jump off that wheel.

So, I did. I jumped. And I didn’t crash into a tree or anything else. I landed on my feet. But nothing turned out as I expected or planned.

An interlude with lasting impact

This journey started many years ago, back in my last year of business school in my native Sweden.

As my parents were teachers, an academic path was always a given. It was not even discussed, never questioned. From the start, I’d bought into society’s prevailing narrative of success: study hard, get good grades, land a good job, get a mortgage, and save for retirement—the whole enchilada.

My strongest motivation to do anything different was to leave Sweden and see the world. I don’t know where it came from, but I’ve always wanted to see more and experience more. Anything that allowed me to do that while checking all the boxes in my life plan suited me just fine. If I had any sense of purpose, it was merely to get out — and fast.

But then, in the year of completing my bachelor’s degree, I struggled with some exams. It felt like I’d failed myself, and for the first time, I began questioning whose dreams I was trying to fulfil. Was it me who wanted to do this, or just what I thought society expected of me? What about my upbringing caused me to expect this of myself?

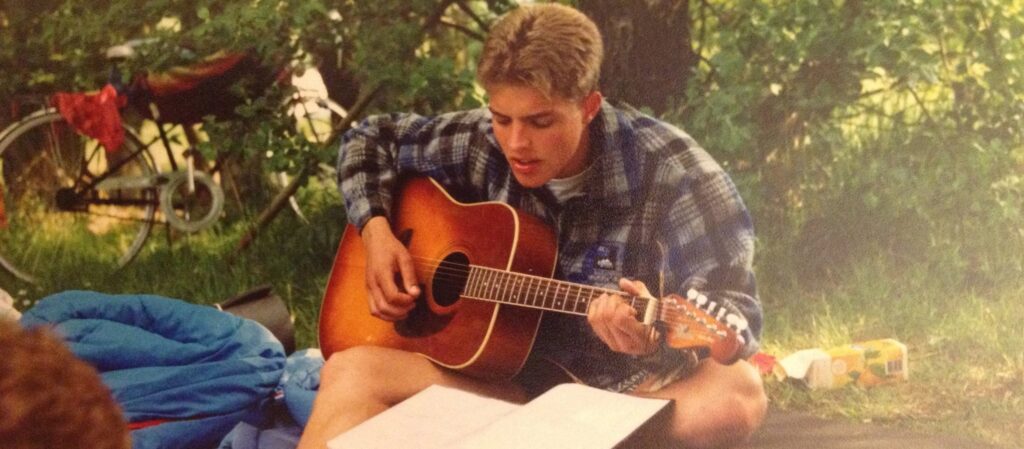

These questions and the sense of failure led me to take a sabbatical and attend a year of guitar school.

Yep, you heard right—guitar school.

In the summer of 1993, my dream of becoming a musician was still alive.

I moved to London and started at the Guitar Institute of Technology. To say I was the odd man out and that I didn’t fit the guitar school mould would be an understatement. For one, I was probably one of a few students who’d completed high school. I was probably the only one not to spend every waking moment practising scales in my room. The other thing I didn’t share with my classmates was talent. They had it in spades, whereas… I enjoyed playing the guitar. So, I accepted that I’d never be a rock star and moved on.

But it did me good to be in an environment unlike the one where I’d spent my entire life and to encounter backgrounds and dreams that were so different from my own. And it planted some seeds that wouldn’t blossom for another two decades. But, at the time, it didn’t change anything.

I finished my sabbatical at guitar school and then had a free semester until my last year of business school. With nothing else to do and thinking it might be fun, I accepted an offer from a colleague of my parents to substitute teach international trade and accounting at a high school.

The two-week stint turned into a month and the entire semester.

It was my first taste of teaching — the first time I felt the excitement of seeing a student get something and grasp things from a new perspective — and I liked it. Indeed, were it not for the lack of career progression and the fear of getting stuck in Sweden, I’d have liked to be a teacher. But my ambitions were bigger, and I returned to university to do my master’s degree, with no real change in my own perspective. If anything, my semester in guitar school and my semester teaching were mere interludes in my planned trajectory: opportunities to take a break, nothing more.

Quitting a guaranteed career

The questions I’d started to ask myself before beginning guitar school had drifted away and then disappeared altogether. I was following a plan rather than following any purpose in my life. And that stayed the same: good school, job, and retirement. Any sense of inner purpose remained out of sight and out of mind. And so, in 1998, I graduated from business school and landed in the management trainee program at a large Scandinavian consumer goods conglomerate.

My life plan entailed climbing the career ladder and creating a comfortable spot for myself. But, as I mentioned, one constant factor that didn’t entirely fit with this plan was my desire to get out and see more of that world. So, when the management trainee program ended, I left that guaranteed career path and took a job in Amsterdam at the IT firm, where I’d eventually find myself driving to work, dreaming of crashing my car into a tree.

But everything had started well. I worked in sales. We had a great, young pan-European team with similar life ambitions, and everything buzzed with energy. Soon, my career took off, and within a few years, I ran that $100-million-dollar sales department. I’d even won an award for best account manager in Europe and found myself on stage in the U.S. with the global CEO and other important people. I thought I was having the time of my life.

Except I wasn’t.

Accepting an award from JC and his crew at Universal Studios in Hollywood, 2003.

Accepting an award from JC and his crew at Universal Studios in Hollywood, 2003.

I was working hard, putting in hellishly long hours building and expanding my team while telling myself that all the hard work would pay off in the future — when I’d be a global CEO. When I’d reached the top, my trajectory was taking me there, and then I’d get my reward.

Except my colleagues at the pan-European level didn’t remotely inspire me. The place where they’d worked themselves toward didn’t seem a happy one. And the place where they’d reached in their lives — working incessantly and neglecting their families and their dreams — didn’t inspire me either. And I felt like I was joining them in the same uninspiring place.

From the outside, of course, I‘d made it. I’d left my little hometown. I had a good education. I travelled, I was living abroad, worked for a great IT company, earning good money. I was starting to become a bigwig. I had a wife whom I loved. We had a daughter whom we adored. Everything should have been perfect. But on the inside, my heart was crying — though I didn’t know yet for what.

And once again, those thoughts that had led me to guitar school started to creep up on me.

“Was this it?” I wondered. “Was this all there was to life? Was this what I was working so hard to achieve? Whose dream is this, anyway?”

My workload at this point was crushing me. An iron yoke pulled me along and dragged me down as the invisible hand of my plans whipped me relentlessly forward. Meanwhile, my colleagues were smiling and laughing around me, giving each other high fives. I thought to myself: “Am I the only one struggling here? Am I not cut out for this? Am I not good enough?”

I couldn’t accept that, so I worked harder and harder. It reached the point where, on the last day of my 2005 summer holidays, I was sitting in my parents’ garden, talking to my father and lamenting that I had to return to the office on Monday.

I wanted an escape. A way out. At the very least, a break. But the birth of my daughter and having a new family to support didn’t allow me the luxury of another sabbatical. That autumn, I started contemplating those trees on the road to work, thinking about ending up in the hospital and finally throwing off the yoke of work, at least for a while.

Escape, lawsuit, and vodka

I mentioned initially that my career path didn’t end up as expected. I’m a thoughtful, careful, and sensible man by nature and not given to rash behaviour. So, I quit the IT firm, but not with a bang. Instead, after a few more months of grinding away, a friend suggested that we both jump off at the same time and set up an IT management consultancy, which we did once we’d secured our first client.

Initially, being an entrepreneur thrilled me, and in the first 18 months, we secured a couple of big-name accounts and hired six consultants. But my heart wasn’t in it. My business partner was, and is, a highly driven and successful entrepreneur passionate about building businesses regardless of the sector. But for me, now, in retrospect, the project was more of a means of escaping corporate employment than a way into something inspiring.

On top of all this, my relationship had become strained, and I was beating myself up for putting us in this situation. Leaving corporate to set out on my own, I had pulled my wife away from her exciting career and an environment with lots of friends and put her in an apartment in a new country with a language she didn’t know, without friends or family around, taking care of our baby daughter while I was away all day “entrepreneuring” without bringing home much money.

Then, 18 months into my entrepreneurial adventure, the thing I treasured the most — my marriage — was falling apart. A significant client refused to pay us, and we ended up in a legal battle, possibly losing all our work and being left with empty hands.

After three sleepless months, the client finally understood what was right. But my wife and I decided we needed a fresh start to heal ourselves and our marriage, so we moved to Prague, my wife’s hometown. I exited the business I had helped to build.

To cut to the chase, I got a consulting contract back at, of all places, the IT company in Amsterdam. That carried us through the relocation and starting anew in Prague. Then, the financial crisis hit in 2008, and my contract was cancelled only a few months after I’d started.

After six months of unemployment, I took a strategy job at a telecom company in Prague. Not long after, I felt the familiar stress building up in me again. Soon, I found myself stopping by the corner shop on the way home to down an aeroplane bottle of vodka as a way to decompress and then going through a pack of chewing gum so my wife wouldn’t notice.

Unfortunately, the vodka was followed by a bottle of wine at home, and this became a habit, day after day, week after week, month after month. Things, as I said, weren’t turning out as I’d expected, and I found myself back on the same hamster wheel, the same worn path I’d been on for most of my life, this time with the added weight of too much alcohol and some extra years pushing me down.

It was then that I promised myself I’d quit the corporate world for good by 40, only four years out. But how to do that? As I said, I’m a sensible, rational person.

My escape route first emerged while doing consultancy for the IT firm I had worked for in Amsterdam, to which I owe a huge debt for teaching me a lot, building my resume, and helping me finally leave corporate employment.

One of my assignments there had been to coach and mentor junior sales managers, and I’d quickly discovered a deep pleasure in helping people. It reminded me of my semester of teaching at the high school.

Now, some years later and once again finding myself utterly worn out, it seemed like coaching could be a way for me to heal and maybe even a way of jumping off the corporate treadmill. I’d finally found some meaning beyond working for the idea of a more fulfilling future.

The first steps to exploring purpose

Once again, My lucky break came from the very corporate world I was trying to escape when a global networking company offered me a position. The job was a breath of fresh air — this was a smaller, younger, more vibrant company without all the stifling bureaucracy — but the bitter taste of my time at the telecom company remained.

I hadn’t forgotten my promise to quit the corporate world when I hit 40. Yet, as the sensible man I am, I realised this might be financially challenging, so I decided to explore coaching and get my professional coaching accreditation seriously. It would thus be something to keep me sane should I be too afraid to honour my promise and quit.

So, for the next year, twice a week, I’d get up to have a virtual training session with an Asian coach training company between 5:30 and 7:30 in the morning, then wake my family and start my workday.

And what a fantastic experience it proved to be. As much as I was learning about how to coach others, my mentor took me on a journey to explore who I was, digging deep into my motivations and fears, helping me hold conversations with that little devil perched on my shoulder, who kept whispering in my ear: “You can’t do this. You’re not good enough. People will laugh at you,” and more.

I found the tools to work with all the symptoms of something being quite right. The questions about whose dreams I was pursuing, the feeling of failing at the IT firm, and the conflict that had raged inside me for so long — and still was.

These factors, combined with an interest in Buddhist philosophy and meditation, which had been growing inside me, prompted me to join a small Buddhist community for regular meditations. Conversations with a Buddhist priest helped ground me in who I am, and I started to think about my purpose for the first time.

Simultaneously, from my conversations with friends and colleagues, I realised that I had a lot to offer other people. And so, what had for so long been a fog of poorly defined and fleeting ideas scrambling in my mind became a clear vision of wanting to use my experience to help people overcome the challenges that I’d had, to reconnect them with who they truly are and create a path towards living it.

Except, I had no idea how to make that happen.

Walking in the light of purpose

That answer came from my coaching accreditation, which gave me the confidence to start working with clients. Eventually, this led to partnering with Oxford Leadership and, in turn, opportunities to go into large companies and work with leadership development until, a few years past my 40th birthday, I left corporate employment behind to dedicate myself full-time to explore my passion and purpose.

That answer came from my coaching accreditation, which gave me the confidence to start working with clients. Eventually, this led to partnering with Oxford Leadership and, in turn, opportunities to go into large companies and work with leadership development until, a few years past my 40th birthday, I left corporate employment behind to dedicate myself full-time to explore my passion and purpose.

It was such a relief: the dissonance between the life I had been living and the life I wanted to live had become so strong that the consequent pain had become unbearable.

In doing so, I finally feel that I am, if not yet fully expressing my purpose, at least walking in the light of it. And on my path here, the corporate years served me well; I wouldn’t be able to do what I do now without them.

I’m also grateful for all the role models of the life I don’t want to live that I’ve met over the years. They have unknowingly pushed me to explore my path to avoid my biggest fear in life — ending up as a grumpy old man, bitter for never really having lived.

And please don’t get me wrong: walking on purpose doesn’t make life easier, but I find that it does make it simpler. I see my way forward, and even if the exact path is unknown, my heart is discovering and exploring it.

Reflecting on my inner journey, I now have a sense of coming home to who I am. I can now show up 100% as me, no longer feeling that I must assume roles to fit in or withhold parts of me like I often felt back in corporate.

My current understanding of my purpose is to help create a sustainable and inclusive world, one conversation at a time.

At the centre of this lies nudging people towards new perspectives of themselves and their world, facilitating the integration of their Self and unlocking courage to be who they deep inside know they could be.

This could mean inviting a single person to explore and own their shadow sides, uncover motivation in their heart rather than from outside expectations, or be more conscious of what they support with their spending.

It could also mean working with a room full of corporate leaders on how to pursue a purpose beyond profit and have a sustainable and inclusive impact on the communities their business touches.

Whether with one or many, it’s one conversation at a time. It is a conversation that’s taken me half my life to have — first with myself and now with others finally.

May you also walk in the light of your purpose.

========

An earlier edition of this text was first published as one chapter in a book about purpose written by consultants in Oxford Leadership community. 22 authentic and bold stories — some you may relate to while others you may not. Perhaps some of the stories will inspire you to reflect in ways that are surprising. It’s all welcomed because our intention was to move you through the sharing of our individual personal stories — regardless of the direction it takes you. More about the book here.

The title of this story is borrowed from Ethan Nichtern’s book ‘The Road Home’. A fantastic book that has had profound impact on how I relate to myself and my world. Thank you Ethan.