Even if you are only remotely interested in personal development and leadership, you could not have missed the empathy train.

Empathy is in every leadership conversation now and often touted as the magic key to great leadership, partially because of the rapid rise of Brenéity, the devotion to the teachings of Brené Brown.

All the talk about empathy is well-intended and it’s a good starting point for talking about evolving leadership but I experience two issues with how the term empathy generally is used.

- It’s based on a misunderstanding of what empathy is and what it leads to.

- From my experience working with leaders, the popular idea of empathy is actually quite often causing anxiety and resistance, making it even harder, especially for the leader already struggling, to create emotional connection

They underlying issue is that empathy is confused with compassion. Empathy and compassion are distinctly different, including on neural level activating different parts of the brain.

By shifting beyond empathy we can not only overcome the challenges associated with empathy but create even greater prosocial behaviours and positive feelings for others.

I’ll get back to this but let’s first clarify the terms.

From sympathy to empathy to compassion

The meanings and differences between empathy, sympathy and compassion has changed over time and is somewhat contentious. Checking the dictionaries, you’ll even find opposite understandings of the words.

I suggest we go back to ancient philosophy to explore and clarify the terms and seek practical guidance.

Sympathy comes from the Greek words sym- (with) and pathos (feeling) so the root meaning of sympathy is ‘with feeling’. This suggests that sympathy is the ability to relate with feeling to another person’s state.

Empathy comes from the Greek words em- (in) and pathos (feeling) so the root meaning of empathy is ‘in feeling’. Thus, empathy means to be in the feeling of somebody else, the ability to feel the other persons emotions as if they are your own.

A clear distinction between sympathy and empathy

If your colleague is sad about not getting a much sought-after promotion you can cognitively make a connection to when you were passed over, when you didn’t get elected captain of the sports team, or similar. You cognitively understand your colleague’s feeling of sadness, cognition with feeling.

Sympathy is cognitive relatedness to the other person.

This presupposes that you both share the same idea of advancing towards the top is important. It’s difficult to have sympathy for a situation you can’t relate to.

If your colleague is sad about the death of his cat and you’ve never had a pet, nor ever shown interest in pets, then it’s challenging for you to relate to your colleague’s feelings.

Sympathy creates weak, if any, emotional connection as the experience stays cognitive.

Empathy is then “the next step”, to go beyond cognitive relatedness and to feel with as if the feelings are your own. When your colleague cries over his missed promotion you sit next to him, feel his pain, and feel your emotions dwelling up. You’re experiencing his pain as yours.

Empathy is to feel with the other person as if the feelings are your own.

As a side note, the Swedish language actually makes a clear distinction between sympathy and empathy. The Swedish word for sympathy is medkänsla (with-feeling) and empathy is medlidande (with-suffering).

Empathic hangover and emotional burnout

To be in feeling with people can be exhausting and if you’re a very empathic person you have may experienced what is called empathic hangover.

Dr Judith Orloff describes empathic hangover as “energetic residue left over from the interaction” and if not handled it will impact your physical well-being, gone too far it may develop into chronic emotional and psychosomatic fatigue.

This is supported by research performed by Professor Tania Singer, a world leading scientist at the Max Planck for Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Science, suggesting that empathy is a major cause behind the high level of sick-leave and burnout in health care.

It’s compassion you want to give and receive

Seeking guidance on the root meaning of compassion from Greek doesn’t return anything and the later Latin language points to something very similar to empathy: com- (with) and pati (suffer) so it adds confusion rather than clarity.

I suggest we look east to Buddhism instead, a wisdom tradition where the practice of compassion is central to all branches of Buddhism.

In Mahayana Buddhism, one of the two main schools of Buddhism, compassion (karuṇā) is one of the two qualities, the other being wisdom (prajña), to cultivate on the path to enlightenment.

The most known practice of compassion is probably mettā meditation, translated as loving-kindness meditation or simply compassion meditation, popularised in the West by the mindfulness movement.

Dalai Lama describes compassion as belonging to ”that category of emotions which have a more developed cognitive component.”

Not cognitive as in sympathy, which is cognition with an emotional component, but cognitive as in “on the other side” of empathy.

Sympathy => Empathy => Compassion

Empathy is the gateway to compassion but the two comes from completely different places.

Empathy focuses on the suffering of the other person whereas compassion focuses on the care for the other person.

Compassion is a feeling of loving-kindness and a desire to alleviate the suffering of the other.

Neuroscience strongly supports the shift from empathy to compassion

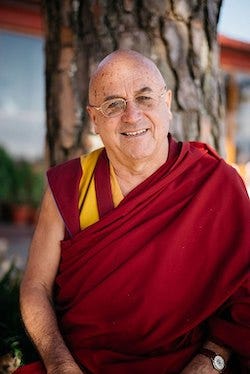

Tania Singer and her colleague Olga Klimecki studied the difference between empathy and compassion on neural level by studying non-meditators, novice meditators, and Tibetan monk and experienced meditator Matthieu Ricard using both a brain scanner and interviews to collect data.

Starting with two groups of non-meditators the first group of participants were asked to practice empathy, to be in feeling with the other person, and they showed activation in the parts of the brain (insula and anterior cingulate cortex) linked to emotion, self-awareness, and consciousness .

Furthermore, interviewing this group of participants they found empathy uncomfortable and worrying, leaving the experiment more unsettled and anxious than before the experiment.

The other group of participants were asked to practice compassion and they showed brain activation in the medial orbitofrontal cortex and the ventral striatum connected to learning and reward in decision-making and in the interview they shared feeling kinder and more eager to help others compared to those in the empathy group.

These results encouraged Singer and Klimeck and they conducted further studies on novice meditators and expert meditator Matthieu Ricard to scientifically back their hunch.

Singer and Klimeck summarise their findings:

“Empathy was accompanied by negative affect and stronger activation in the neural areas involved in negative affect and empathy for pain. Generally, compassion training strengthened positive affect, prosocial behaviour, and neural activity related to affiliation, love and positive emotions.”

I’ve seen some writing and talking about compassion fatigue but it’s clearly a misunderstanding, probably by confusing empathy with compassion.

Singer and Klimeck concludes with:

“It therefore seems that while empathic resonance may led to empathic distress, compassion offers a trainable strategy for increasing prosociality and overcoming the adverse experiences by strengthening resilience.”

Compassion is less awkward than empathy

Going back to my experience working with leaders who find empathy in their professional role challenging.

Their hesitation is often along the lines of: “How do I do empathy? I can’t mirror the others person’s emotions, especially not in the workplace. If the person is sad, I can’t sit and be sad next to them. It will be silly. But everybody talks empathy now so tell me how to approach this?”

Often it is simply that it’s a new behaviour, they’ve neither seen empathy role-modelled by their leaders nor any public display of “weak” emotions at work.

The shift that releases tension

When we talk about shifting from being in feeling with the other person to feeling appreciation for the other human (not merely the role they represent) and a desire to help them overcome their challenge it’s a lot less threatening.

With this shift from empathy to compassion is not about a “public” display of emotions but genuine appreciation and care for another human, which can be done authentically without sobbing shoulder to shoulder.

And as science confirms, it’s a lot more effective in creating prosocial behaviour and positive affect than empathy.

A shared aspiration

Coming back to what I said in the beginning, there are many different definitions and explanations of sympathy, empathy and compassion so you can probably find references to argue the very opposite of this article. That’s fine.

If you spend the time to do this it means you have reflected on these ideas, internalised them and hopefully started practicing them.

Let that be the our aspiration, irrespective of our definitions: to express appreciation and care for each other.

__________________________

See this pdf document and this blog for more on the study by Singer and Klimecki. I highly recommend Brené Brown’s books ‘Daring Greatly’ and ‘Dare to lead’.

— — — — —

I’ve recently released three workbooks to support you in making sense of the weird and wonderful journey of life and leadership.

I also host weekly virtual meditations in the Rinzai Zen tradition, on Mondays 20:00–21:00 CET and you’re welcome to join us. More info here.